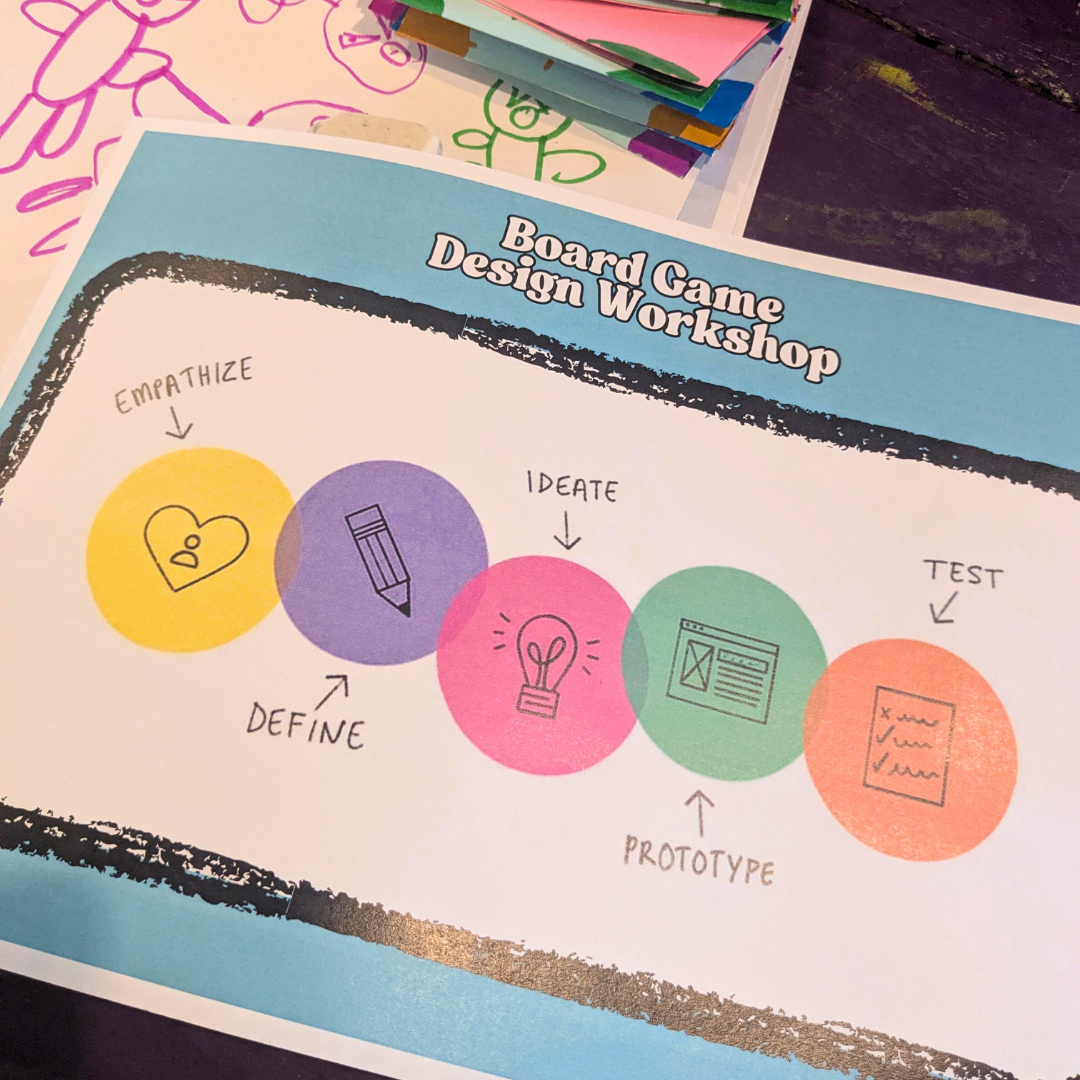

Design Thinking is a human-centred problem-solving approach that emphasises empathy, creativity, and continuous experimentation to develop innovative solutions. It plays a vital role in designing everything from software applications and medical devices to administrative systems and new business models. But can such a powerful concept be introduced to children at a young age? Is it possible to shape a child’s mindset to think like a real-world designer?

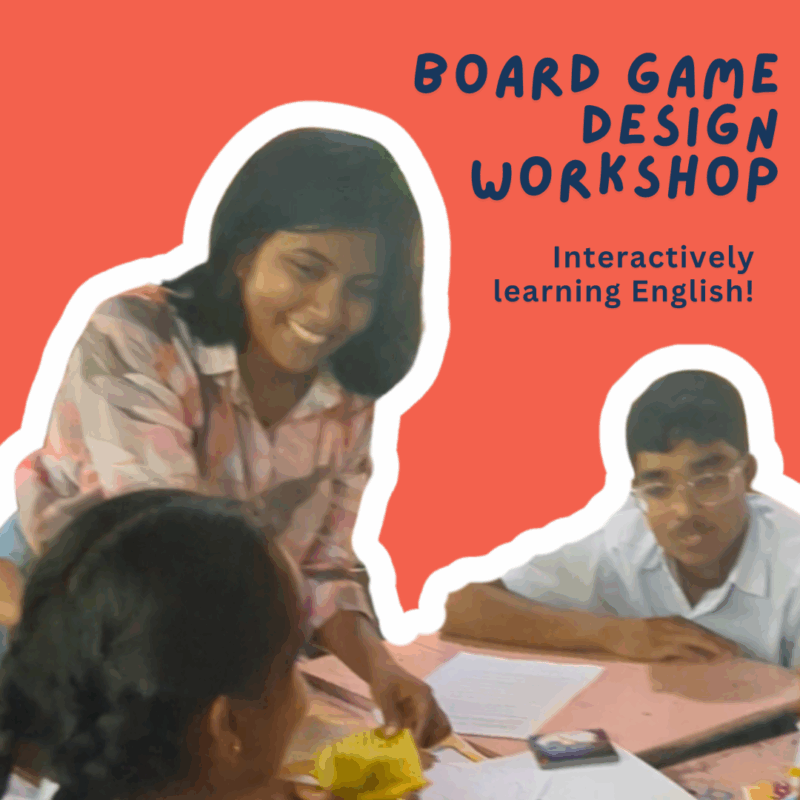

These were the very questions that inspired us to create a Board Game Design Workshop for kids, aimed at introducing the concept of Design Thinking through hands-on, practical learning. If you think about it, designing a board game is a powerful and accessible way to teach the full life cycle of product development, especially to children.

Kids aged 8–12 may not yet have the technical skills to build software, and working with hardware can be expensive, time-consuming, and complex. But board games offer a simple, tangible alternative. They allow young learners (and even adults) to explore the fundamentals of human-centred design in a fun, creative, and engaging way—right from identifying a problem and empathising with users to prototyping, testing, and iterating.

This is why we were so excited about hosting our Board Game Design Workshop at Independent Collective School on 8th May 2025. A heartfelt thank you to Mrs. Yasodhara Pathanjali, who, without hesitation, welcomed the idea and supported us in making this workshop a reality.

We had the pleasure of working with twenty enthusiastic students aged 8 to 13 who joined us for this creative experience.

After a warm introduction, we began by guiding the kids through the basics of board game design and the core ideas of design thinking. We were careful to keep our language simple and relatable, using everyday words to explain complex ideas, so that the children could understand the concepts without getting stuck on the terminology.

To help the kids ease into the session and open up, we needed an ice breaker—and the first step of the Design Thinking process gave us the perfect opportunity:

Empathize

Empathise is all about understanding the user—observing their behaviour, listening to their experiences, and gaining insight into what they enjoy or struggle with. It’s the foundation of designing meaningful, human-centred solutions.

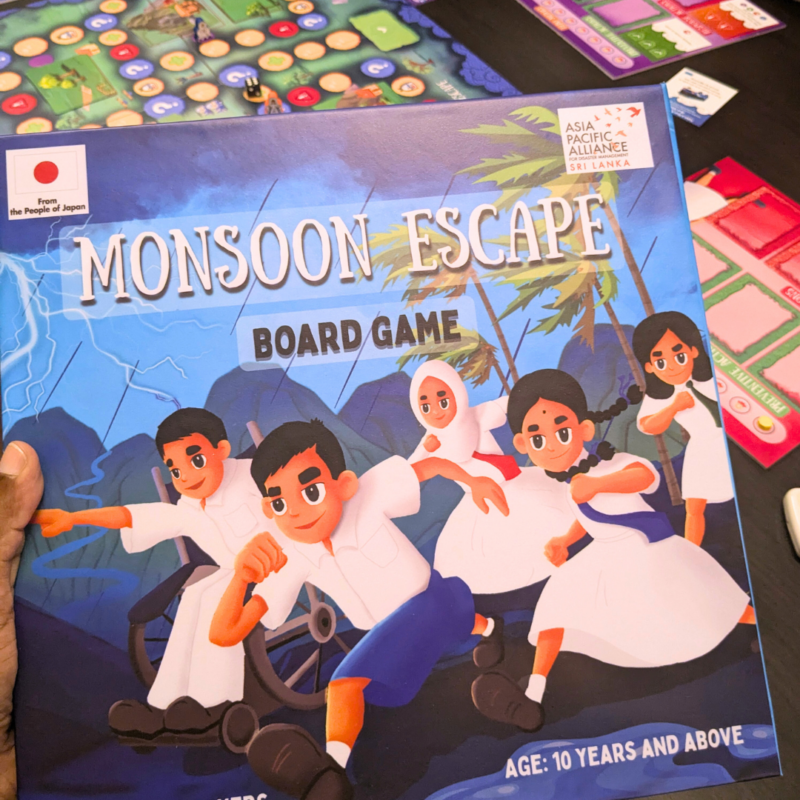

To begin, we asked the students about the board games they’ve played before. Some had tried more advanced games like Catan, Monopoly, and Chess, while others weren’t as familiar with those. But everyone knew Snakes and Ladders—a timeless classic from their early childhoods. So, we chose it as our starting point.

We handed out Snakes and Ladders game sets to each team and asked them to play. But this time, they weren’t just players—they were designers. Their task was to observe the game critically and think about how it could be improved, all the while they were playing it.

This subtle shift in perspective—seeing the game not just for fun, but as something designed—was a new and exciting experience for many of them.

And we were genuinely surprised by the depth of empathy they brought to the table.

After playing, each group shared their observations. They noted things like: “The game feels too short.”, “It gets boring after a while.”, “It’s too easy—there’s no challenge.” etc.

These insights were not only thoughtful but pointed us clearly toward the next phase of the design thinking process: understanding what could make the game better.

Define

The second step of the Design Thinking process—Define—is where children begin to shape their initial ideas into a clearer direction by framing a challenge or design problem. This step isn’t about jumping to solutions, but about identifying what they want to design and why.

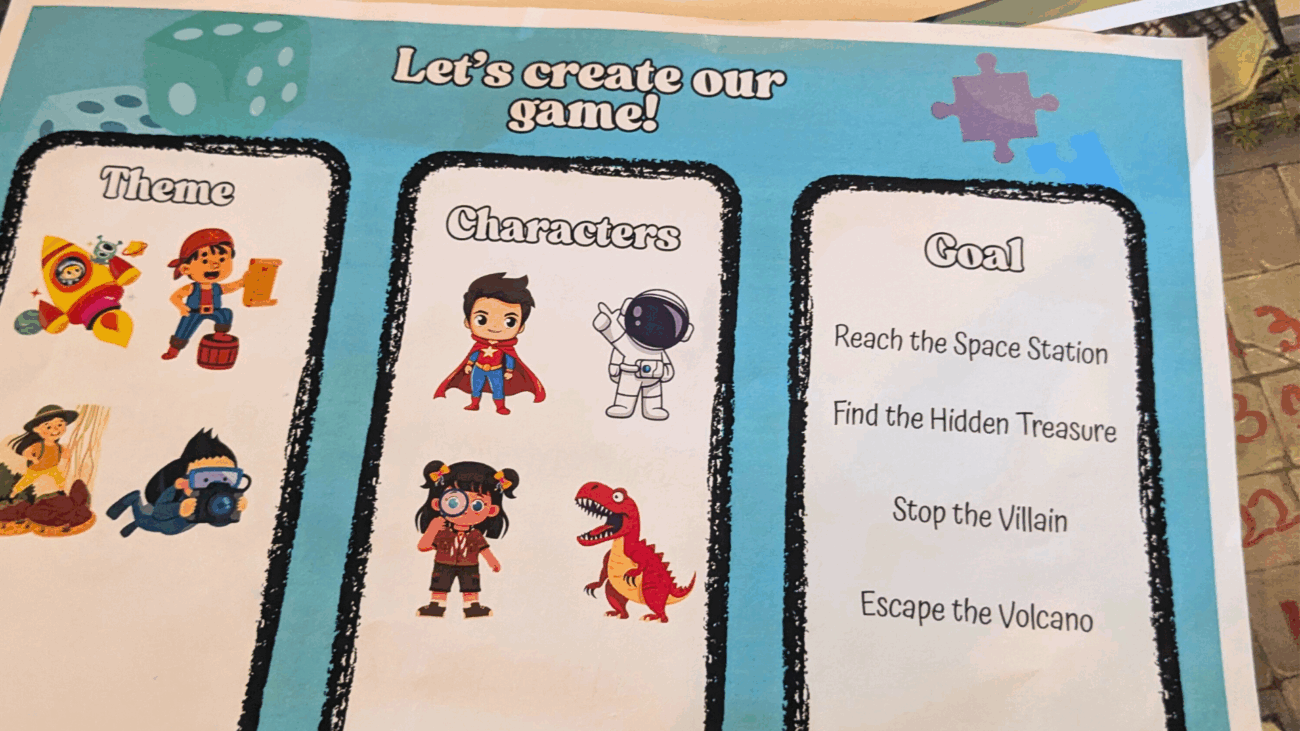

Of course, expecting children to articulate a clear game design immediately would be unrealistic. Even adults take time to arrive at a concrete idea. So, to guide them in defining their vision, we gave them prompts to help their creativity find form. We first encouraged them to think about the theme of their game. Would it be about pirates on the high seas, a thrilling space race, surviving in a world of dinosaurs, or an underwater treasure hunt? By thinking about the world their game would take place in, they began to define the overall feel and direction of the game they wanted to create. Then we asked them to decide on the end goal. What would players try to achieve? Was it escaping danger, reaching a hidden treasure, or battling their way to victory?

The responses were delightful and full of imagination. One group envisioned a high-speed space race, complete with aliens poking fun at players along the way. Another imagined a dinosaur-filled world that included combat as part of the gameplay. A third team designed a jungle adventure where players collected coins and fought with swords, all while trying to outrun an erupting volcano. The youngest group surprised us with a wildly creative battle between pirates and zombies.

Although their ideas were full of excitement and originality, the students were still unsure of how to bring those ideas to life as functioning games. This is exactly where the next step—Ideate—comes into play, helping them brainstorm and explore how their imagined worlds could become real, playable experiences.

Ideate

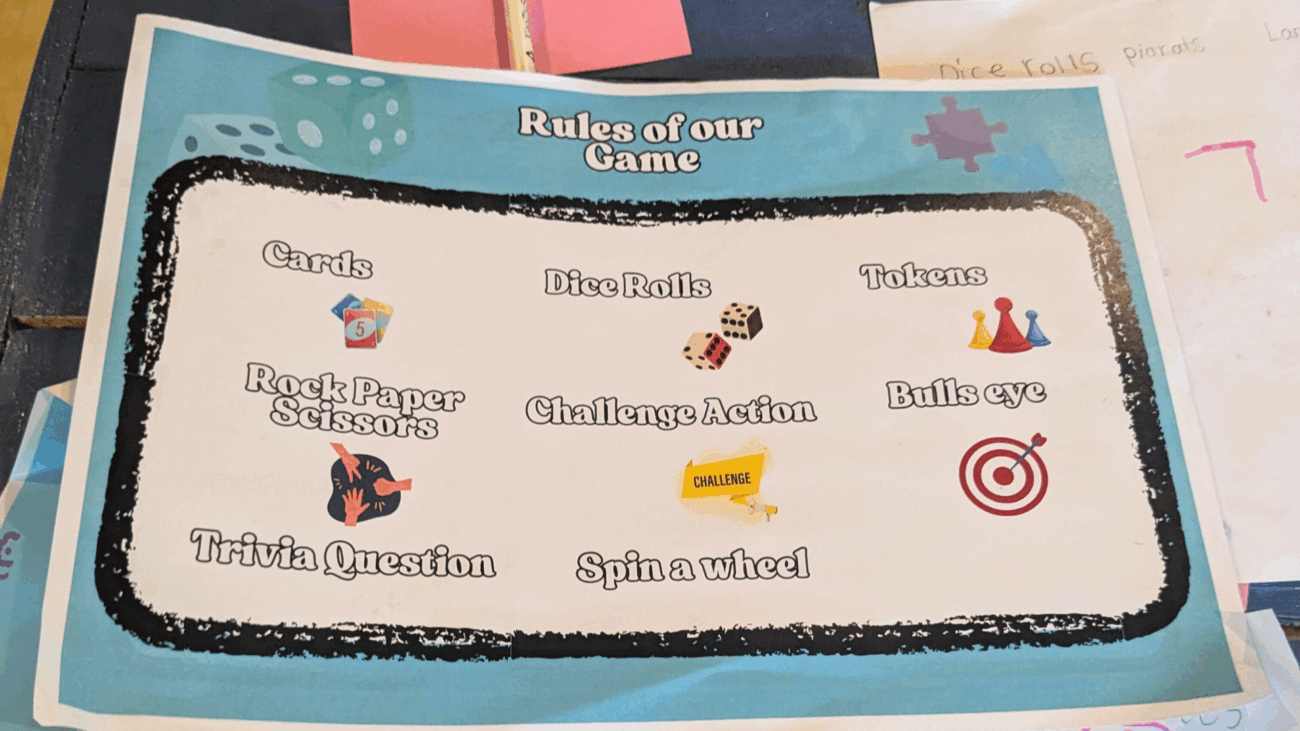

The third step of Design Thinking, Ideate, is all about letting ideas flow freely, encouraging creativity, experimentation, and thinking beyond the norm. This is where the students began to explore how they could bring their defined game concepts to life by imagining unique mechanics, rules, and gameplay experiences. With no restrictions, their imagination took centre stage.

We prompted each group to think beyond the traditional rules of Snakes and Ladders and consider what mechanics would best suit the themes they had chosen. The dinosaur team, who had envisioned a game with combat, introduced a fun twist by incorporating a rock-paper-scissors challenge whenever two players landed on the same square. This created player interaction and added excitement to what was once a very passive game. They also decided to ditch the traditional dice in favour of a random card selection system, designing their own themed cards to match the prehistoric setting.

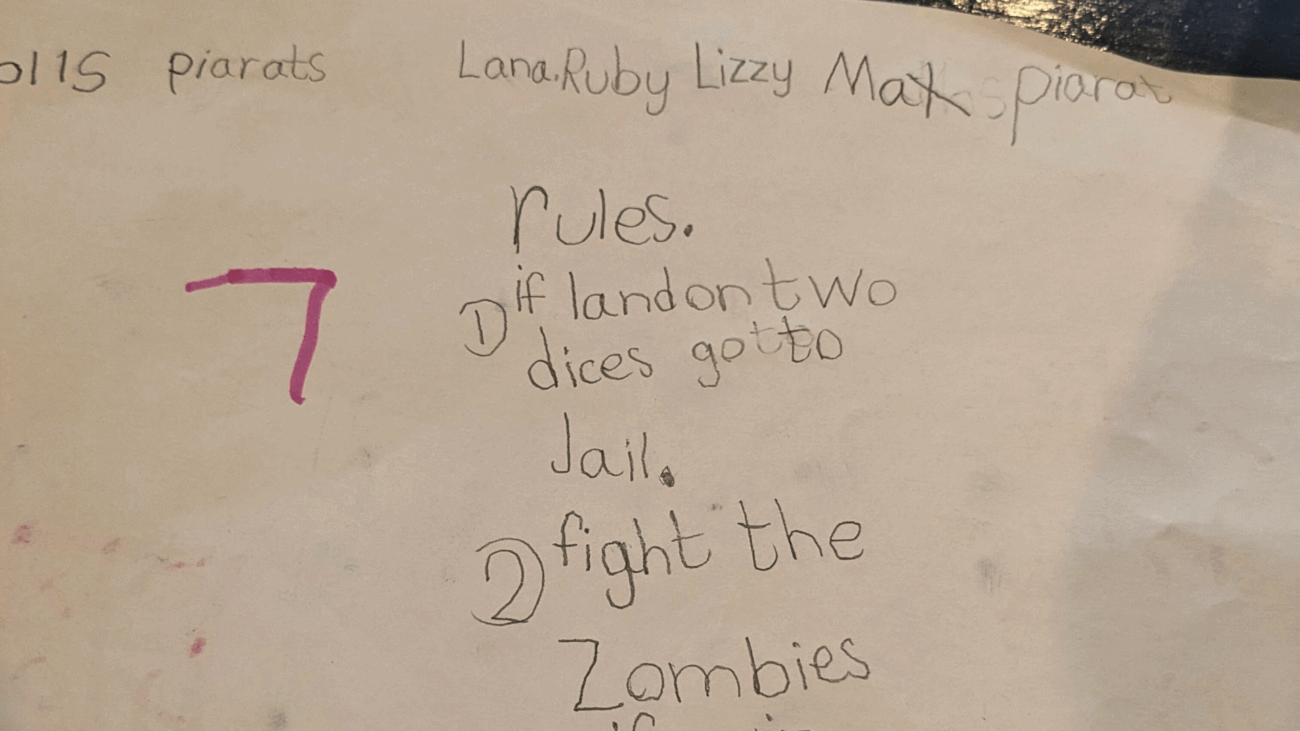

The pirates-versus-zombies team took a clever approach by modifying the dice mechanics altogether. They opted to use two dice instead of one, introducing new movement combinations. They even created a “jail” square inspired by Monopoly: if a player rolled double sixes, they were immediately sent to jail and had to roll another pair of sixes to get out. It was a clever and challenging mechanic, especially in a world where pirates were constantly fending off the undead.

The space race team, on the other hand, aimed for a more streamlined experience. They reduced the number of squares on the board to speed up gameplay, ensuring every move counted. Instead of rolling the dice, players drew cards with different colours, and each colour corresponded to a space on the board. This allowed players to zoom ahead or fall behind depending on their luck, making the race fast-paced and dynamic.

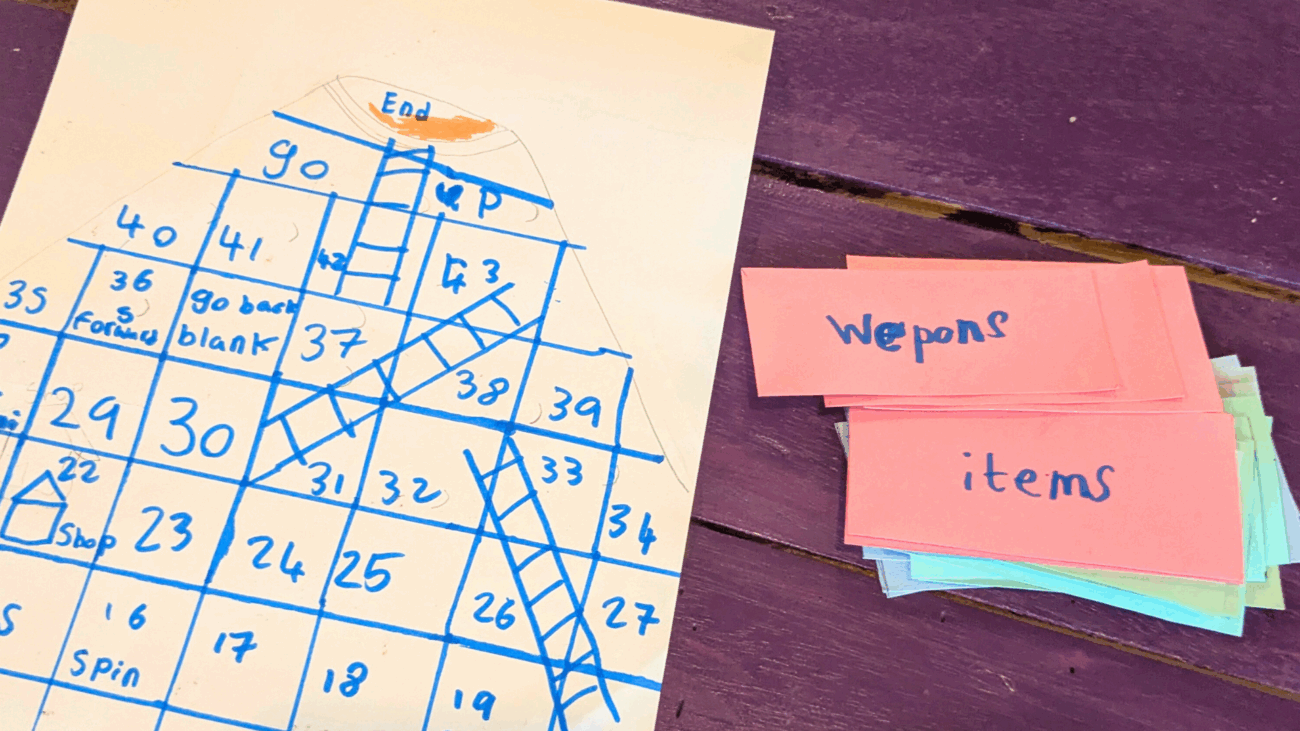

Then came the volcano explorers team, who fully embraced the spirit of innovation. They introduced a card collection mechanic that allowed players to gather swords, weapons, and coins as they progressed through the game. They redesigned their game board to resemble a volcano, adding visual excitement and dramatic flair. Certain squares triggered special challenges, and to make things even more thrilling, they created a spinning wheel that allowed players to win different items depending on where the spinner landed. Their game quickly evolved into a multi-layered adventure filled with unexpected twists.

By the end of the Ideate phase, it was clear that the students had begun to think not just like players, but like true game designers. Each team developed original, creative systems tailored to their chosen theme. However, ideation can be mentally taxing, so we knew the kids needed a change of pace—a chance to get creative in a different way. That’s where the next stage of the Design Thinking process came in, offering them the perfect opportunity to bring their worlds to life visually.

Prototype

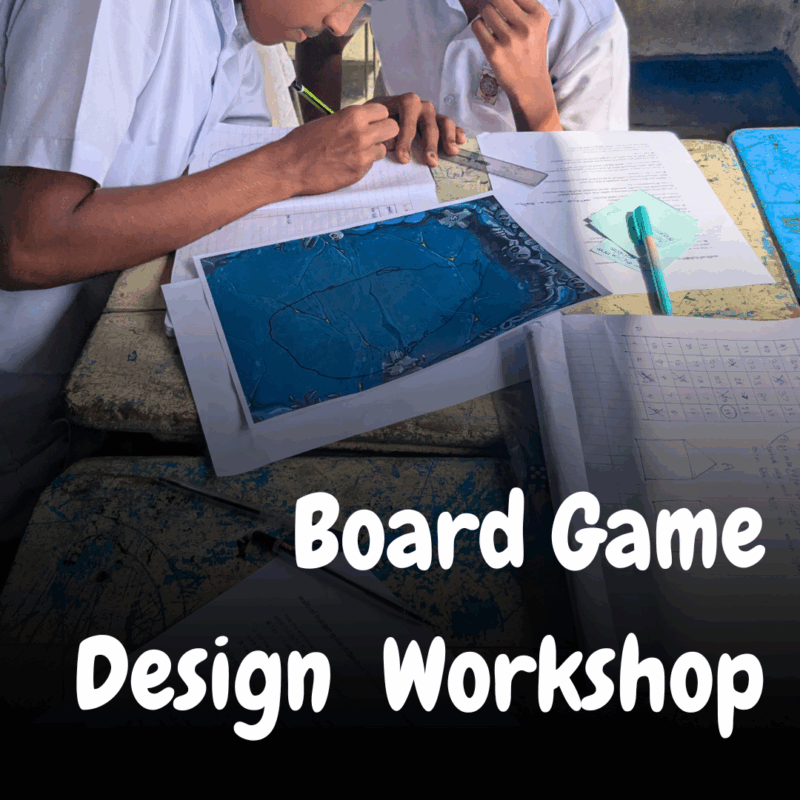

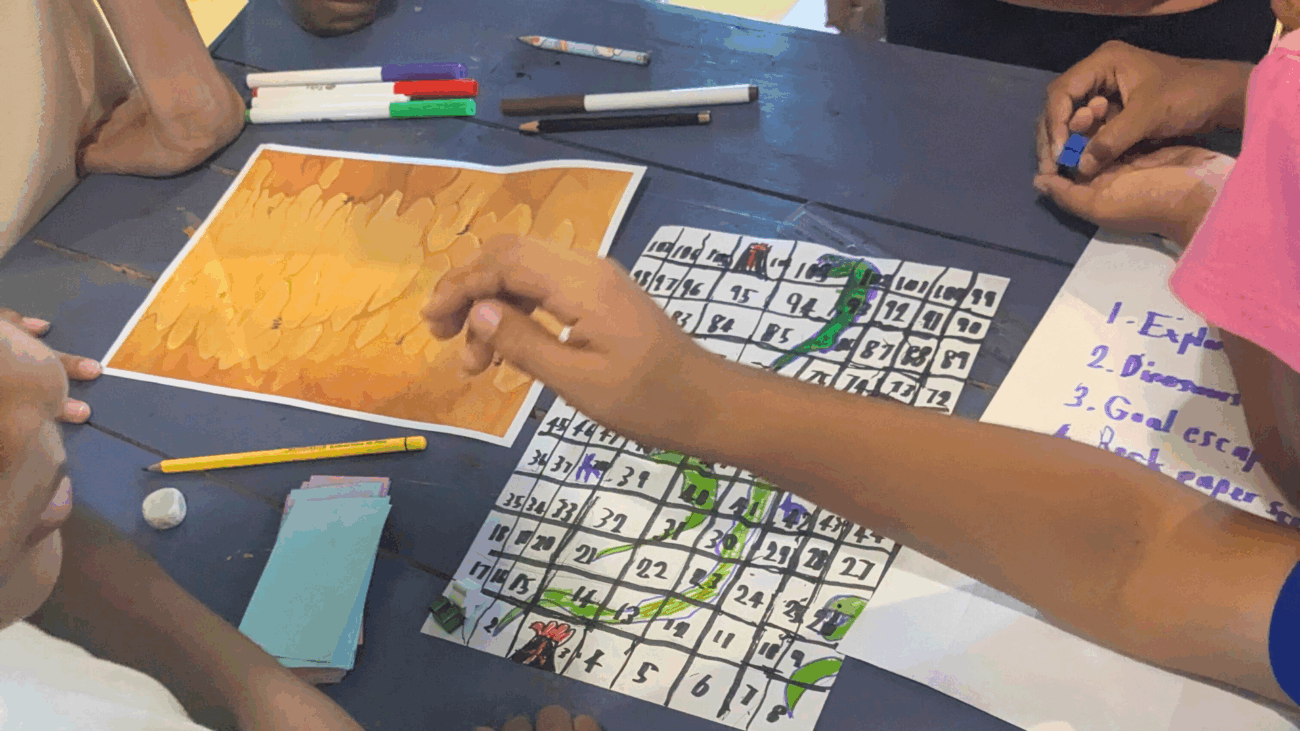

The fourth step of Design Thinking, Prototype, is all about bringing ideas to life in a tangible form—quickly and creatively. This is where imagination meets reality. What makes board game design such a perfect fit for the design thinking process is how easily it lends itself to prototyping. It doesn’t require expensive tools or technology—just paper, pens, a bit of time, and a whole lot of enthusiasm.

During this stage of the workshop, children began translating their ideas into real, playable designs. Armed with colored paper, markers, scissors, glue, and plenty of creative drive, the kids began constructing game boards, writing game rules, and designing their custom cards.

Each group had their own approach. Some spent extra time carefully illustrating every detail of their board, like volcanoes ready to erupt or dinosaurs in mid-combat. Others focused more on the cards, using colored paper we had pre-cut for them and writing out item descriptions, power-ups, or special actions. A few teams even took their creativity a step further and started writing out the rule books for their games, making sure anyone who picked up their prototype would know exactly how to play.

What mattered most in this phase was not perfection, but functionality—creating something that could be tested and improved. Despite the time constraints, the students were determined to have their games ready for the next phase. The excitement was building. They weren’t just playing anymore—they were designing, creating, and preparing to share their work with others. And with the Test phase just around the corner, they were about to discover how their ideas would hold up in the hands of new players.

Test

The final step of the Design Thinking process is Test, where users interact with the prototype and provide feedback. This is the stage that often opens everyone’s eyes. You might believe your idea is flawless, but it’s only when someone else plays it that you truly discover what works—and what doesn’t.

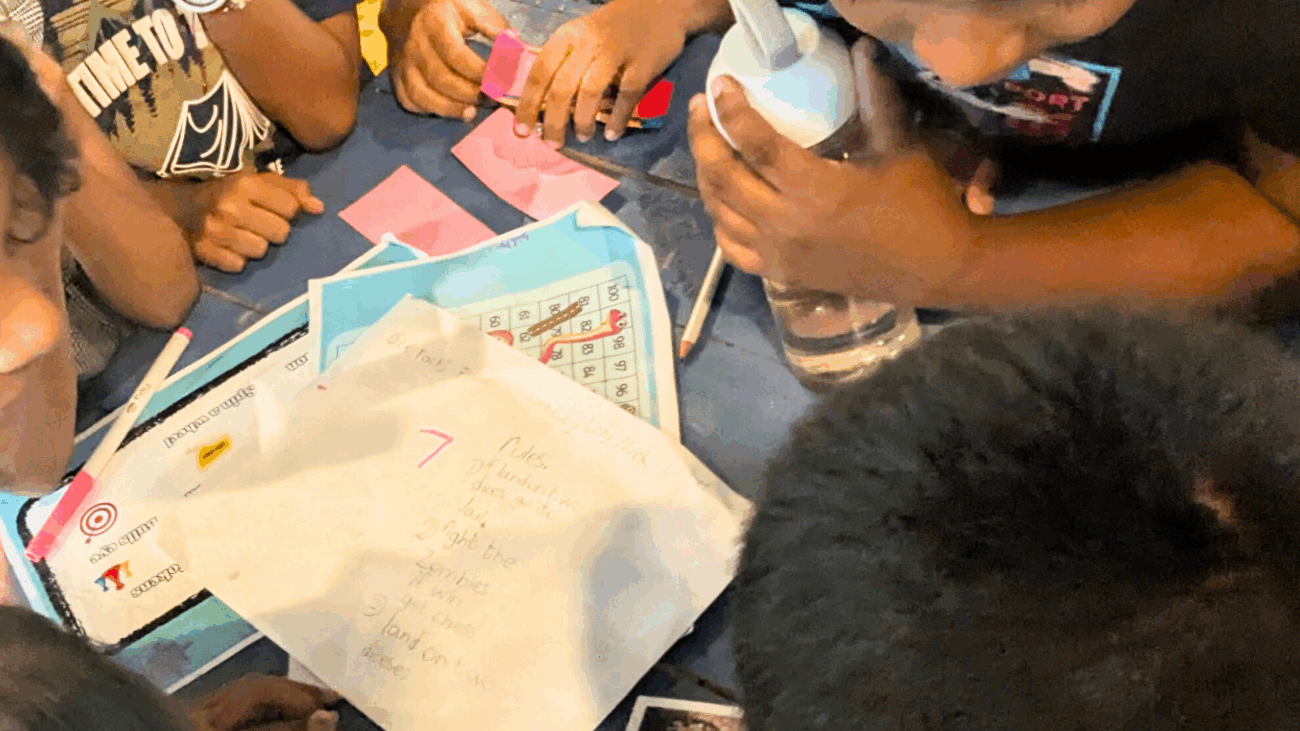

In the workshop, testing became a lively and insightful activity. Each team was paired with another. One team would introduce and explain the game they had just created, guiding their peers through the rules and how to play. Then, the roles would reverse, and the other team would get their chance to showcase their game.

It quickly became clear how valuable this step was. Some game mechanics worked wonderfully; others needed a bit of fine-tuning. For example, one team’s spinning wheel feature looked exciting on paper but proved tricky to execute with the materials they had. Meanwhile, the space race game was a hit in terms of speed, but players felt it needed more challenges, like mischievous aliens, to make the game more unpredictable and balanced. These observations were not criticisms; they were learning opportunities. The kids realised just how important it is to look at their designs through the eyes of others.

This exchange of feedback also brought out a sense of pride and appreciation for each other’s work. The students admired the detailed drawings, clever ideas, and inventive gameplay that their peers had come up with. Many of them expressed a desire to continue improving their games at home, showing how invested they had become in what they created.

Though time didn’t allow for full iteration cycles, the spirit of Design Thinking—empathise, define, ideate, prototype, test, and repeat—was truly experienced. The children left with a deeper understanding of how great ideas evolve through testing and feedback. Many took their games home, eager to refine them with fresh ideas from their families.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the workshop was the collaboration between the students. The task of designing a board game was divided among the team members, which helped manage time efficiently and allowed everyone to contribute their strengths. Kids who excelled at drawing took charge of the artistic side, while others focused on designing the game board. Some team members brainstormed ideas for collectable cards, jotting down their favourite concepts after discussing them with their peers. This division of labour fostered teamwork and creativity, as each child played a crucial role in shaping the final product.

What came out of this workshop was a powerful demonstration of how a process often seen as complicated, like design thinking, can be introduced to young children in a fun and engaging way. Not only did the workshop teach the core principles of the process, but it also allowed the kids to experience each step practically.

Overall, the workshop provided a unique opportunity to craft something special while applying a human-centred design approach. It demonstrated that even complex problem-solving processes can be accessible and enjoyable for kids, leaving them with a deeper understanding of how to approach challenges, collaborate, and think creatively.